Part of a talk given at the Grosvenor Museum, Chester, on 11 November 2023 as part of the Chester Contemporary events programme.

Introduction

As archaeologists, we move from the known to the unknown. We start with a thing and work to understand it for itself. Then we widen our gaze and add that thing to other things to try, eventually, to create new knowledge about complex past worlds. Archaeology, the way we understand both the things and the complex worlds, takes many forms. It is the trenches, the trowels, the measuring tapes, the theodolites, the laser scanners, the magnetometers, the isotope analysis, the papers, the journals, the conferences, the lectures, the books, and the television shows. But as well as those things that archaeologists make and use, archaeology is also in us. The difference between two soils, invisible to the eye, but felt and understood in our bodies, transmitted by the extension of the arm via a trowel, into an act of scraping. It’s there in the feelings and hunches, the choice to look one way and not another, the decision to communicate, how, when, and with whom. Those archaeologies that happen within us are all-important because, of course, not only does all archaeology happen today, in the moment, but all of the past and all of the future exist in the present too. So when we are doing those existential archaeologies of looking and feeling, what we are doing is simply being in proximity to all time, and trying, if we choose, to make sense of that, and maybe even do some good with it.

The works of Chester Contemporary are archaeology. They are archaeology in that they are things we can look at, feel, and attempt to understand. They are also, separately and together, a tool for us to understand Chester’s past and future; not facts about the past, not stories from the past, not specific hopes or predictions for the future, but how multiple pasts and futures exist all around us today. It’s vital that we take these chances to understand that because pasts and futures are neither fixed nor passive. They are fighting for attention, sometimes by themselves. Our knowledge of the past, for instance, is largely directed by those things that persisted, and refused to decay. So when I tell you that Chester Contemporary is one of the most important archaeological events in Chester’s history, you shouldn’t be surprised.

Chester Contemporary has complicated the way the past exists in contemporary Chester and artists and archaeologists all, we can gain a lot from putting ourselves into the middle of Chester Contemporary and the things and experiences it has created, and use that to understand what it is to be a person in this historic place. You may wish to use that understanding to simplify things. My preference, as it has always been through, now, multiple decades as an archaeologist, has been to use archaeological knowledge to try to come to terms with standing on the edge of an abyss containing all of the past, all of the present, all of the future; three things we can barely make out, let alone understand. Fleeting glimpses from the edge of everything is all we have.

Nature & Geology

Sometimes we need to pull back from the edge of that chaos and order things just a little, so I want to talk about some particular artworks and their archaeologies. By coincidence, they fit chronologically, from the ‘oldest’ (for the sake of brevity today, I will stick to linear time) to the youngest, but they also work as scales, from grand and worldly to minute and personal.

So we will first stand and appreciate Harry Grundy’s The Mingling Tree, a potted olive tree travelling around the miniature railway in Grosvenor Park, in places brushing leaves with its soon-to-be neighbours. As with many of the Chester Contemporary works, there is a great beauty to this act. Trees are Chester’s oldest living inhabitants, some of them living a wild life of random seeding, pollinated by wind and insects. Most of the trees in Grosvenor Park came to be with notably less agency, but still, this is a place of nature in the city centre, dominated by the kinds of things that were here before Chester. To welcome a new tree, to introduce it to its fellows, to draw attention to it and its, we may say person-like, needs in this way, is a very beautiful thing to do. It reminds us that in and around the Chester of people, there is an equally complex Chester of non-people that know each other, live with and for each other, who have bonds that will be in place when everyone in this room is long gone. Grundy’s tree will outlive us all, and it will carry into the future the memories of having once been at the intersection of human and non-human worlds, of the brevity of a journey around the miniature railway, and scales of time in which people and their cities are but a moment.

Elizabeth Price’s HORSETAILS takes on these temporal scales, taking as its subject geology and its meeting with humans at the point of mining and extraction. To date, this work has been performed in three forms with a full choral working still to come. Chester Cathedral is a perfect setting for the work because inside there, you are surrounded by geology, most of which has been extracted, shaped and reformed into arches, columns and walls, even representations of people, but some of which is undergoing a process of creation as people buried below the cathedral floors slowly return to the earth.

We are surrounded there by the geology at the centre of Price’s work, but that geology is active, being pulled and pushed by physical forces, yet arranged in such a way as to largely deny them. Sitting listening to Horsetails took me back 18 months to being in the cathedral watching the film Once A Desert by Heinrich & Palmer, a film which also spoke to the deep time origins of the building materials surrounding us, in this case 200 million years back to the Triassic. Once A Desert made much use of a wireframe scan of the cathedral building and at one point we, the audience, are taken shooting up the inside of one of the cathedral’s columns. This is, obviously, not a real viewpoint, but it is a real place, inside geology, inside structure from the point of view of physics, soaring skywards to challenge gravity. Price’s own work takes us on a similar journey, speaking the names of places and stones, words and music bouncing off the very geology it references to help us experience the piece, and through the piece, the place.

Undercurrents

Layers, and the interfaces between layers, are incredibly important in archaeology and they feature strongly in Chester Contemporary too. Works by Simeon Barclay, James Lomax and Nick Davies speak to ‘what lies beneath’, to those temporal undercurrents which occasionally expose themselves to today.

Lomax’s placing of striped tarpaulins brings memories of Chester’s historic markets into the present city, a space of uninterrupted commerce since the medieval period. The tarpaulins, ostensibly randomly placed do not just refer to that past, but remind us of the trajectory of that history. Closed shops may be distressing to the City and its people for months, years, but within a thousand year history, those shorter times are as nothing. Lomax’s tarpaulins tell us that things will be ok.

As we face uncertain futures, we, as people and as a city, are willed on by hundreds of thousands of traders across time, with whom we share our streets. Lomax’s Markets Shift Like Sand V has them peeping through windows, watching us as we walk, shop, hurry and worry.

Nick Davies work A Sweet Connection, Sorry Paul (Way After Gottetsday) references the artist’s own childhood, but is placed to also remind us of a forgotten piece of Chester’s history, the Shrove Tuesday football match that took place on the Roodee, though its referencing of a punch by the artist also brings to mind the so called ‘pitched battle’ fought here in 1441 between Rokley and Hooley, the gaolers of the Castle and the Northgate, the county and the city. A place of sport then, and a place of violence, and a place of violent sport. It is not only history that lies beneath, but other things too, violence being one of those undercurrents most likely to burst through to the surface.

But there are other dark undercurrents too and Simeon Barclay’s Them Over Road tackles them head on. Them Over Road is in three locations, in each of which neon words hang enmeshed with parachute fabric and cords. Those words are Bitter, Lost, Hero, Boys, Bruised, Aloof, Arrogant, Flacid, Pose.

Of all of the Chester Contemporary works, Barclays is, to me, the darkest, the most menacing. In part, this is because of its locations, the basement car park, the empty shop, places where we have to work to find the piece and see it properly. But it’s also menacing because of the message of the work, that Chester’s focus on heritage is at odds with its aspirations and the ways in which a diverse range of people use and live in it, with which we may disagree. And that’s uncomfortable. It’s a view of Chester from the outside that isn’t really found across the rest of the Contemporary, but which, having found it, as archaeologists we cannot ignore.

Chester Contemporary, whether we see it as an archaeological section, a literary palimpsest or a geological melange, takes times other than now, past and future, and reveals to us how they exist in the present day, as legacy, memory, reference, hope and fear.

The 90s

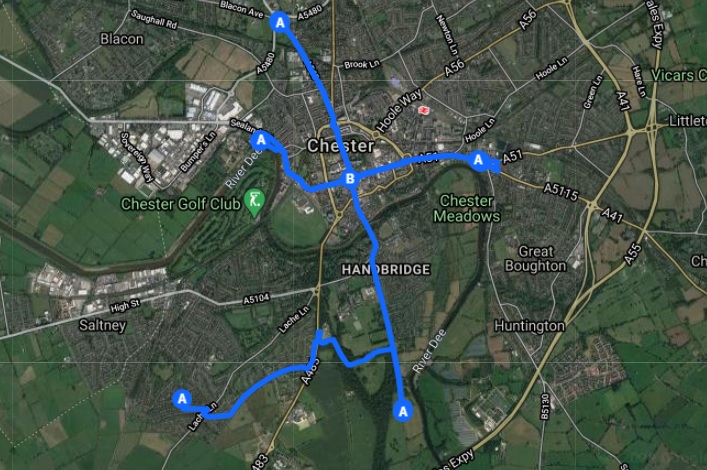

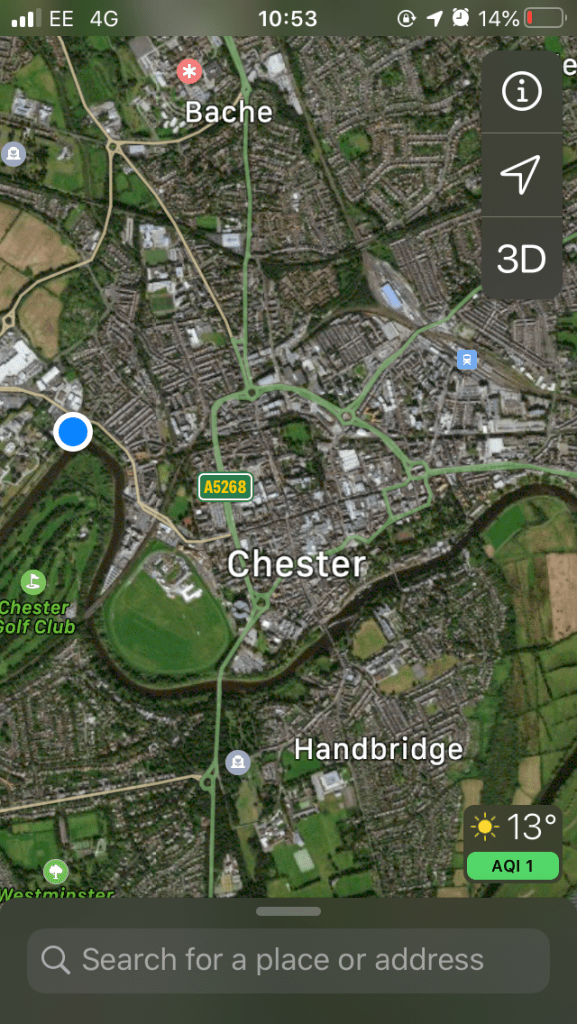

Auto-archaeology is the archaeology of oneself, or explicitly of ourselves. I regularly walk through the streets of Chester listening on the Spotify app on my phone via wireless earphones, to the same music I bought in those streets on CD in the 1990s, and walked around listening to on my Discman. The archaeology of the 1990s is there in me every time I walk through town, but it’s also there in the works of Hannah Perry and Jacq Bebb, who both grew up walking through Chester at more or less the same time I did.

Perry’s No Tracksuit, No Trainers is a comment on being a working class woman in the contemporary art world, but it’s also a memory of growing up in Chester and having to meet the sartorial requirements of the bouncers outside Rosies. It’s also about the act of remembering.

Stand in front of one of Perry’s silver sheets and you will see a blurry reflection of yourself looking back. The soundscape begins with a low rumble, causing your reflection to pulse and shake, and as the vibration builds, you see yourself and your world transformed. To be here, there, today, on one day within a life, within a whole history of place, and to be confronted by the conflict between certainty and confusion, the latter exacerbated by Perry’s sensory experience, is to get to the heart of your own Chester, and of art as archaeology. No Tracksuit, No Trainers takes you out of time, and after seeing it for the first time, you emerge from that underground depot into a different Chester to the one you left. The nightclub experience Perry references is the one point in common I have with Cestrians anywhere in the world. When we meet, and speak, Rosies is where we begin. As archaeologists, we work from the known to the unknown. We stand at the door of a nightclub, with the countless others who have been and are still to come, and from it we understand our world.

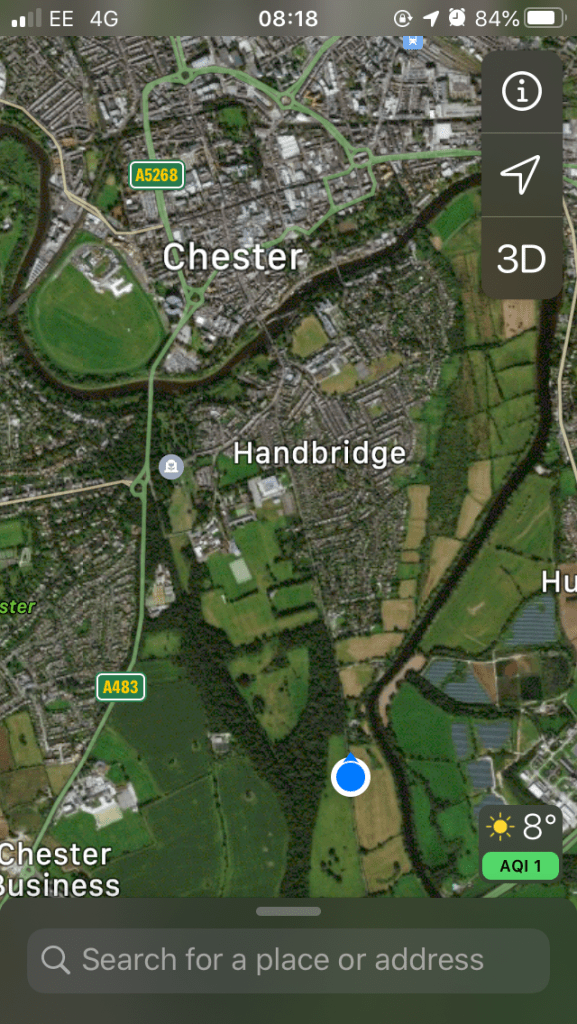

Jacq Bebb’s artistic practice, which they call ‘skulking the in-betweens’, parallels my archaeological practice of walking, looking and feeling, putting myself into places both known and unfamiliar, to see what stories they want me to communicate to others. Bebb’s Queer Time, a sound installation which takes as its inspiration 1990s memories of hanging around not getting into a nightclub on Watergate Street, changes your experience of that street. When we are going from shop to shop, from home to work, from a to b, or from the known to the unknown, the going doesn’t have to just be a means to an end. It has its own experiences, its own meanings, its own value. I first heard Bebb’s sound work with Jacq Bebb, having arranged to meet there. And the second, third, fourth times, I watched the clock and went intentionally to hear it. But then I heard it by accident, killing time in the city centre waiting for an event to start, I wandered along Watergate Street only to hear Queer Time playing up on the Row. I hadn’t expected it. I had, for that moment, forgotten it. And to have that aimless moment interrupted by Bebb’s work, their memories… well, I laughed out loud. Bebb’s work comes from skulking, and it’s best heard mid-skulk. It’s a reminder that you don’t have to get where you think you’re going to have a story to tell.

Conclusion

So… Chester Contemporary is archaeology and not only that, it’s a key part of how we understand Chester’s pasts as they exist today. The ways it does that are not, perhaps unique. We don’t need artworks to trigger memories, or describe our surroundings. We don’t need artworks to make us feel. We don’t need artworks to create juxtapositions, expose undercurrents, or question what we think we know. But artworks are great at doing those things because the way we experience those things in relation to artworks is usually unexpected. So we are not just dealing here with archaeology, we are dealing with great archaeology, archaeology that reaches inside us and rearranges our very being. It’s important too that all of this art-archaeology is happening at the same time. For the duration of Chester Contemporary, whether you experience it for two months or for a day, that feeling of delving, scraping, thinking new things and feeling things you didn’t expect to feel is made overt, and it’s not just you feeling these things as you notice something odd on your way to work, it’s all of us together noticing things at the same time. So it’s not just great archaeology, it’s great community archaeology too.

We are not finished here today. There is more to be said. But when you leave here, I suggest you walk the Contemporary again, but think about the spaces between those artworks as well as the pieces themselves. Find other bits of Chester that tell the same stories as Jacq Bebb and Hannah Perry. Find other bits of Chester that unsettle you as much as Simeon Barclay. Find weird spaces and imagine what new things you would put in them. Then, you will be my kind of archaeologist, looking at your own worlds and your own lives in ways that might just astonish you.

Chester Contemporary is not just a thing that happened. It is contemporary Chester. We can all be contemporary archaeologists and as contemporary archaeologists we can take those knowns, our memories, favourite places, buildings and artworks, and work from them to an infinite unknown universe, all here in our little city. And that’s exciting.

Email jamesdixonresearch@yahoo.co.uk for more information.