This paper was published in the Journal of Chester Archaeological Society vol 94

Introduction

Why is public art so important to archaeology and heritage? Permanent public artworks can be treated like any other remains of the past, telling us something about the context of their creation. As they also go on to exist through time after their creation and installation, the world may change around them in ways antithetical to the imagined future for which the artworks were intended, or even change in response to an artwork, sometimes in big ways like creating new destinations or driving tourist numbers, or more usually in small, almost imperceptible ways such as making people walk differently through a town, think differently about where they live, or prompting them to grumble on social media. Temporary public art and performance does the same thing, but in a slightly different way. People are still able to engage with artists’ interpretations of the places where they live, situated in those landscapes in ways that, intentionally or not, chime with or rub against how they feel and what they think they know. But then they are gone and they may or may not be missed. In contrast to most permanent installations, with temporary public art people experience the arrival of the piece and all that goes with that, and its loss. Whether temporary artworks are missed or not when they go, and the ways in which they live on in how people feel about and understand the places in which they live, says something about the interpretations that the artworks represented and how they are part of the present and future. Moreover, the temporariness of temporary artworks creates artistic intervention as an event, forcing people to think about all of this now. Complex networks of differing, sometimes competing, pasts, presents and futures are brought into focus, making people think about those works and networks in relation to their own world and lives, and understand a little more of their world in return.

Chester Contemporary

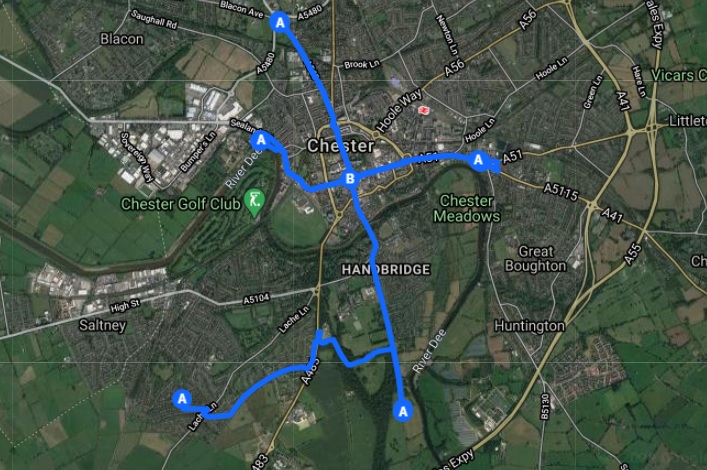

Chester Contemporary (22 September to 1 December 2023) was a visual arts event commissioned by Cheshire West and Chester Council (CWaC). It brought a number of international and local artists, established and emerging, together in the production of a ‘walking biennial’ curated by artist Ryan Gander OBE RA. Artists were invited to make and show work in Chester’s unique places and spaces, inspired by the theme ‘Centred on the Periphery’. Responses were broad and included installation, performance, voice and film works.

Chester Contemporary can be thought of as an important intervention in Chester’s heritage and archaeology for two reasons. The first, perhaps the most obvious, is that the content of works created for it tell people things about the city and its past, present and future, whether that is the geological formations on and in which the city sits or what it was like to grow up here at the end of the twentieth century. At a more fundamental level, though, it is also possible to learn something from how artists look at the city and consider how artistic practices and the outputs developed from those might usefully be added to the repertoire of approaches and activities available to archaeologists and heritage professionals. These lessons can be useful on a daily basis in moving around the city and observing it as individuals interested in history, heritage and archaeology, but also in projects like the CWaC Local List or Heritage Strategy, both of which can be enriched and reach wider and new audiences by both conceiving of archaeology and heritage as more widely, perhaps loosely, defined, and in encouraging others to do the same.

This short review will discuss a few of the Chester Contemporary artworks, how they can be thought of as a contribution to our knowledge and experience of the archaeology of the city, and how heritage practitioners can learn from them.

Chester Cathedral

Chester Cathedral hosted two performance works that addressed deep time and durational time in interesting ways. HORSETAILS by Elizabeth Price was a choral piece composed in response to the intersections of humans and geology at the point of extraction, the piece naming different stones and their locations in the geology of the area. The piece was performed and re-performed regularly in a number of different forms. Chester Cathedral was a perfect setting for the work, partly as an excellent backdrop for choral work in general, but also because audiences are surrounded by reformed geology in the form of the floors, walls and columns of the building. This is geology that has been extracted, crafted, shaped, sometimes into representations of humans, and assembled into architectural forms. It is also the site of new geology as past residents of Chester, buried beneath the cathedral’s floors, slowly return to the earth. That reformed geology is, of course, active, being pulled, pushed, stretched and compressed, and the performance of HORSETAILS reflected that, both in the duration of each performance and the regular repeating of performances throughout Chester Contemporary. For audiences, whether seeing it once or multiple times, the piece put geology-in-motion overtly into this great architectural space. All buildings are constantly in motion, but to have any space, let alone one as grand and important to the city as the cathedral, activated in this way was a great contribution to how we might understand the city and its structures. HORSETAILS served to remind us that most buildings have deep-time histories contained within their constituent parts and are in constant movement, even if that is largely unnoticeable to us at any particular point in time. The choral performance of HORSETAILS on the launch day of Chester Contemporary can be viewed on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dAuin8o9hss.

It is perhaps also worth mentioning an earlier installation, Once A Desert by Heinrich & Palmer, a video, sound and light installation work shown at the cathedral in 2022. This work also spoke of the deep-time origins of the fabric of the cathedral and included an incredible wireframe scan of the building, with the viewpoint moving around the space and at one point shooting up the inside of one of the massive columns. In this shot the cathedral is experienced from the point of view of the physical forces holding the building together. A short excerpt of Once a Desert can be viewed on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wK6LEzxq8WU.

Also within the cathedral estate, on the Dean’s Field, was Crop by William Lang. Part of the Chester Contemporary Emerging Artists programme, the performance, structured with elements of improvisation, took place on and around a mown square representing the cathedral cloisters. The performance that took place condensed a day in the life of a medieval monk to just over twenty minutes, with elements showing waking, moving in and around the cloisters over the course of the day and finally retiring to the dormitory at the day’s end. A performance of Crop can be viewed on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TiggsB3uDh8.

Two things stood out about this piece, both related to its relationship with its audience. The first was that, attending on the Chester Contemporary launch weekend, it was an incredible experience to be part of a large crowd standing together on the City Walls paying attention to something. Although most visitors to the walls, and local residents too, may occasionally pause to look at something or to take photos, engagement with the walls is usually in motion, so to make people stop and observe for a relatively long time offers a new way of engaging with heritage. Durational engagement is really important. People will always learn more about a place or space the longer they engage with it, and being still for a good amount of time is a very effective way to get to know a place or a building. The twenty or so minutes standing still on the wall by the Dean’s Field to observe a representation of a day in the life of a medieval monk combined two different durational experiences in an interesting way, slowing down experience of the city while speeding up a particular aspect of history. The effect was to unsettle more typical engagements with the past by letting people experience time passing. The result is heritage interpretation that people do not simply consume but of which they are part. Both on the day and subsequently, there have been comments on this piece on social media and made to the author directly from people who ‘had no idea what that was about’. Any response to art is fine, and this is a fairly typical response to contemporary performance from those who have not necessarily experienced work like it before, but it highlights both that occasionally more explicit prompting might be required to help an audience along in their understanding of the content of a piece and that, conversely, there is not always something to ‘get’, not a story that people are meant to follow and understand as in a play. So, while this piece took as its inspiration a day in the life of a medieval monk, the audience was not supposed to come away with a better understanding of that life but of the passage of time (the contrasting passages of time as discussed above), of the difference between their part in the event and the artist’s, and the experience of having stood still in a familiar place and watched an unfamiliar performance happen before them. The intricacies of movement, staging, the physicality of the performance might also be appreciated, all of which were not placed second to any story one was supposed to absorb and remember as they may be in other media. Ultimately, this was a fascinating piece and a type of artwork that could do a great deal to expand and change how we understand and experience the historic city.

Roodee

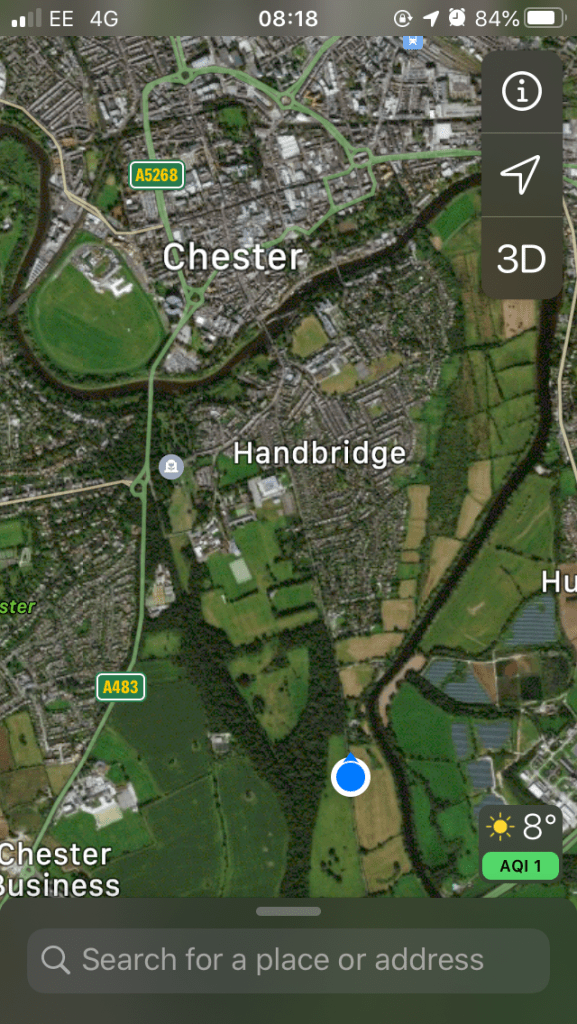

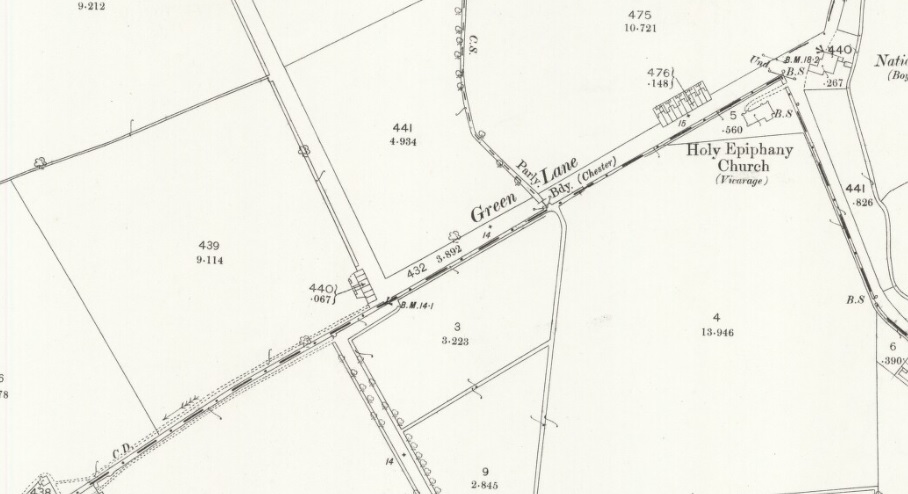

A Sweet Connection, Sorry Paul (Way After Goteddsday) by Nick Davies was located on the Roodee, inside the racetrack. The piece itself was formed of four ‘jumpers for goalposts’ made of casts of clothes and it referred to both the artist’s childhood and the historic football matches played on the Roodee on Shrove Tuesday.

This was, itself, a good piece of heritage interpretation, neatly placing present-day lives into the passage of longer periods of time, perhaps connecting forgotten historical traditions with how people remember, or do not remember, parts of their own lives. However, the work was something more than that when viewed in context in a way that could not perhaps have been foreseen by the artist. Because of heavy rain, towards the end of Chester Contemporary the Roodee was heavily waterlogged with large pools of water on its river side. Already this added a different dimension to the work, as another layer of history became visible. Not only was the work about the present day, the artist’s childhood and about the medieval city, but people could also see a hint of Roman and early medieval Chester in the same space as the former harbour started to reclaim the land. But, stepping back further, one could also observe that the temporary artwork and sodden Roodee were overlooked by formal heritage interpretation in the form of an information board and viewer on Nuns’ Road. The easy juxtaposition between formal and informal interpretation in one location, contrasting in form, but complementing each other’s content, made for a more rounded appreciation of the heritage of the location. However, it should be noted that the viewer is out of use, leaving the visitor to fill gaps in order to understand the site. Altogether this was a fascinating collection of different kinds of heritage interpretation that was enabled by the siting of Davies’ piece.

The Nineties

Works by Jacq Bebb and Hannah Perry were derived from experiences growing up in Chester in the 1990s, a period that might not ordinarily be thought of as falling under the remit of archaeology but which can be fruitfully investigated as well as any other period, with the added interest that most people remember it. Perry’s work No Tracksuits, No Trainers was installed in the old market depot off Hamilton Place and consisted of a number of metallic vinyl sheets hung in front of speakers on metal frames so that they vibrated when a soundtrack was played. The installation also included vacuum-formed car parts and clothing.

No Tracksuits, No Trainers was a comment on being a working-class woman in the contemporary art world but took its inspiration from the door policy at nearby Rosie’s nightclub, the need to own the right clothes to be able to enter, the need to have a car to get anywhere in this part of the world, aspects of the culture surrounding cars and car modification, and the juxtaposition of car parts and the creativity of modification with Chester’s reputation as a heritage city. Viewed as heritage interpretation, Perry’s piece served to highlight aspects of life growing up in and around Chester that more comfortable or older residents, or residents who grew up elsewhere, might not be aware of. The focus on Rosie’s was particularly key as that nightclub a point of connection between Cestrians of a certain age, and many people under the age of thirty who visit Chester will have experience of Rosie’s as well. Thus it was possible to learn something about growing up in the area (and how its restrictions and barriers can be echoed later in life), but also to focus for a short time on a local place that is as important to some people as Browns, the old market or Owen Owen are to older reminiscers.

Also focusing on Chester clubs in the 1990s was Jacq Bebb’s sound installation Skulking The In-Betweens (Queer Time), a trio of recordings playing along the south side of Watergate Street at Row level. The spoken words making up the recordings were inspired by Bebb’s recollections of hanging around outside Connections, an LGBTQ+ nightclub on the street, being too young to go in but wanting to be part of the life that went on inside behind closed doors, and of what being able to go inside represented. Again, there was a focus on a forgotten part of Chester’s recent past as in Hannah Perry’s installation, but Bebb’s work looked at modes of investigation in a way that archaeologists and heritage practitioners can appreciate.

Bebb’s wider body of work often returns to the idea of ‘skulking’, going where the mood takes one, waiting around for something to happen, just being in spaces and places. This is a valuable form of archaeological investigation that all can easily try. Rather than relying on prior research, existing knowledge or guided tours, people can investigate places by simply being in them and waiting for things to draw their attention. There is an archaeological story to be told everywhere, and examining a particular space without preconceived notions of what it is or what one is looking for can take interpretation in interesting directions, where ‘the archaeology’ is more a collaboration between the viewer and the site than something he or she imposes on it as a knowledgeable interpreter or physically extracts as an excavator. Bebb’s focus on ‘skulking’, and their informal installation that could be heard in passing or by accident, also serves to democratise archaeology, removing hierarchies inherent in much of the discipline and its outputs. There are forms of useful and important archaeology that can be done by anyone at any time and Bebb’s skulking is a perfect example of that.

Simeon Barclay

The final piece discussed here is Them Over Road by Simeon Barclay, which consisted of three sets of three neon words in front of draped parachutes located in the window of Chester Roman Tours on Grosvenor Street, inside an empty unit on the Bridge Street Row west, and in the bottom of the car park of Crowne Plaza hotel, visible from St Michael’s Way. The words themselves present something of a challenge to the city; Bitter-Lost-Hero, Boys-Bruised-Aloof, Arrogant-Flacid-Pose.

These words are not the ones we might usually associate with Chester’s past or present and hint at a different story to be told. Barclay’s development of this work aimed to comment on the difference between the way Chester sees itself and the way it is seen, and the ways in which certain sites’ darker sides are written out of popular histories. The choices of Chester Roman Tours and the Rows, for instance, sought to highlight how we take certain aspects of our history for granted. The Rows, for instance, are not simply a benign heritage site in the present, but also a place where homeless people sleep and that has periods of trouble with anti-social behaviour. This is a side of The Rows that have been regularly reported on in local newspapers from their earliest editions but not one that is widely presented beyond Dark Heritage tours. Barclay’s point is that, even though we may seek to end those negative aspects of the Rows in the present and future, by ignoring those other presents and dark pasts we are ignoring a crucial aspect of the history of the Rows, which is that they are conducive to whatever has been deemed anti-social behaviour over at least the last two hundred years and possibly longer. Thus the Chester promoted through much heritage interpretation and marketing in the present day is at odds with crucial facts of its history. It is not to ignore the need to end anti-social behaviour in the present day to say that the Rows themselves enable bad behaviours through their intrinsic qualities of being central but separate, in places partially enclosed, a good vantage point and so on. Chester’s Roman history also has incredibly dark aspects that do not necessarily always make it into popular understanding of the period or the promotion of contemporary Chester as a Roman site. The City Walls, for instance, were intentionally reimagined as an attractive social space in the eighteenth century but were once a physical barrier separating different ethnic groups and political systems, one colonial-imperialist, the other more-or-less indigenous. The Crowne Plaza hotel car park has a more recent history, but is also at the centre of competing narratives, being dug out as part of an imagined future, but now little used.

With his multi-site work, Barclay used this historical commentary as a metaphor for the wider city and its view of itself, perhaps seeing an over-reliance on certain histories that are not the whole story and that have been sanitised. By extension, the work suggests that we need to recognise more of the complexities in Chester’s history and contemporary identity in order to have a strong future as something other than a tourist destination selling a particular view of the past. This was, perhaps, the Chester Contemporary artwork that spoke most directly to the complicated relationship between past and future manifested in the present.

Chester Contemporary and the Future

When Chester Contemporary was launched in 2022, curator Ryan Gander talked about wanting to create a new future for art in Chester. He spoke about there being nowhere for artists to meet each other and that artists who grow up here needed to move away to pursue their art. This is not just Gander’s vision. Chester Contemporary was itself part of a long-running effort by the Arts team of Cheshire West and Chester Council to transform the city’s art scene and strengthen its artistic community. The fact is that there are artists resident in Chester who say publicly that they work from Manchester because it has more kudos. Clearly, one thing that Chester Contemporary showed is not just that Chester can successfully host a walking biennial featuring internationally known artists as well as local talent, but that the works in something like Chester Contemporary can be of a key part of how we understand the city and its past. Chester Contemporary was an important archaeological event for precisely this reason. Not only did it occupy and change spaces we think that we know; it told new stories, told old stories in a different way, and afforded new ways of being in the city as archaeologists and heritage practitioners. Part of how Chester Contemporary changes the art scene in Chester can be how archaeologists and heritage practitioners engage with art and artists, how they take inspiration from the way artists engage with the historic environment and how they communicate with different publics. The future of art and archaeology/heritage in Chester can be seen as mutually dependent when it comes to innovation and developing new ways to look at the world and its pasts. As each develops and innovates, the other can respond. Ultimately, what Chester Contemporary demonstrates is that there are infinite possibilities when it comes to understanding and communicating history, archaeology and the historic environment, and hopefully this will become widely recognised and practiced as Chester’s contemporary art scene grows and is strengthened.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank Simeon Barclay, Jacq Bebb, Hannah Perry, Nick Davies, Carmel Clapson and Emma Knight for discussions about artistic and archaeological practice, both during and since Chester Contemporary.

Chester Contemporary was funded by HM Government (UK Shared Prosperity Fund), Arts Council England, National Lottery Heritage Fund, Henry Moore Foundation, Historic England and National Lottery Heritage Fund. Project partners included University of Chester, Storyhouse, Open Eye Gallery and Edsential.